THE FINE ART OF PAYING ATTENTION

JOHN HANSON MITCHELL is a master of the fine art and deep pleasure of paying attention. Author of Ceremonial Time, Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, a landmark in American natural history writing, among other books, Mitchell also was the editor of Sanctuary, the splendid magazine published by Mass Audubon for 34 years until it was (to me, inexplicably) discontinued last year. You can read a collection of his natural history essays from Sanctuary here.

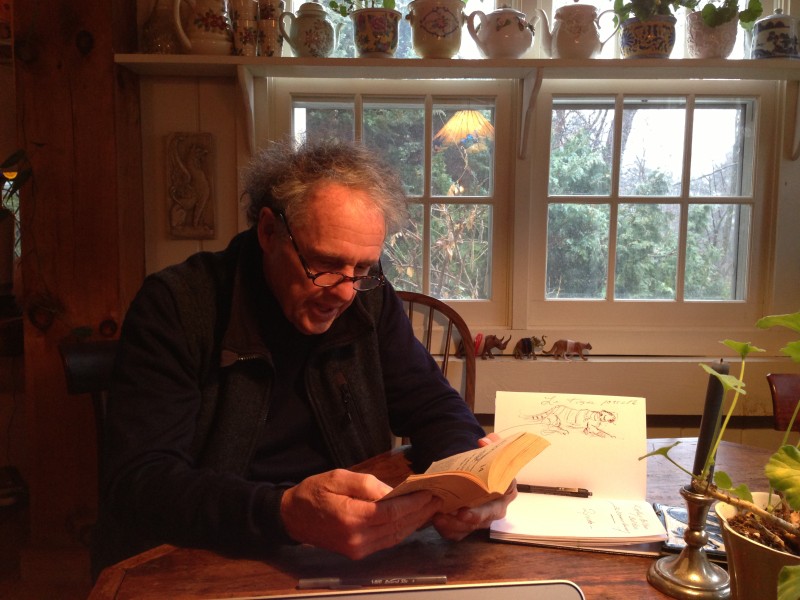

I asked author John Hanson Mitchell if we had the right to do what we are doing to the planet with climate change and he answered “…the judges are the animals.” Note the animal sketched in his journal, and the animals on the window sill at his home.

When I began work on my own book, Witness Tree, last year about the human and natural history of a single 100-year-old red oak at the Harvard Forest, I knew Ceremonial Time, a classic in the genre of deep observation of one place – think Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, or Henry Beston’s The Outermost House — was a must-read for me. It had been in my house, and my husband’s before mine, for many years. I tucked the slim paperback with its venerable, yellowed, crackly pages amid the books we packed when I headed to the Forest last fall to begin a year’s sabbatical year away from my job as a reporter at the Seattle Times, to write the book while a Bullard Fellow in forest research funded by Harvard University and based at the forest.

John Hanson Mitchell’s writing studio, one of several out buildings on his property he has made into personal havens for work and observation.

In his book, Mitchell explores one square mile of America – its life, legends, and 15,000 years of history in what he calls Scratch Flat, an ordinary bit of New England woods and pasture, and his home for more than 30 years. It is one of those books in which nothing happens, and everything happens, and is the story of no place in particular, and therefore everyone’s place – it is about not the grand wildernesses and remote, mystic redoubts of John Muir, but the quotidian places where most of life happens. The places we call home.

So it wasn’t long after I arrived here that I looked Mitchell up, and found him at his home, still in Scratch Flat, on a wet winter day.

What a deeply nested home: the main house was full in an uncluttered way of personal treasures of every sort. But it got better, as Mitchell showed me the collection of outbuildings he has created over the years, one for a writing studio, another a cabin retreat, a third a gazebo for sitting in his carefully tended garden. It is here that Mitchell lives the practice of phenology – the observation of the seasonal progression of nature. Phenology has been rediscovered by mainstream scientists as a way to document the affect of climate change on the land, as seasons change in a warming world. But for most of us, phenology is today what it has always been for people, everywhere: the art and pleasure of paying attention.

Into the garden, his refuge and place of contemplation. Mitchell uses only hand tools — in part to be able to hear the birds as he works.

Mitchell visits the landscapes of Beaver Brook near Littleton, MA, a.k.a. Scratch Flat daily, just as he has for more than 30 years. “It is very peaceful, you can hear the highway on some days, but there are these empty spots here on Scratch Flat…and I go down there and it is total peace. Winter wrens, the pale winter sun, that smoky hazy day like today, it is beautiful with the shades of colors like tapestry. You see more life in the winter, you can see who has been there, fishers and coyotes and deer.”

Watching the progression of the seasons is second nature to him: “It’s how I tell time,” Mitchell said.

The garden is part of how and where he witnesses climate change, in both its day-to-day reality, as seasons change – and how he copes with the fact of it. “You forge on in the fact of it,” Mitchell said. “This thing of a billion other possible planets, that is good news. Maybe it doesn’t matter. The sun is going to burn out. In the history of the universe we are a pretty short-lived phenomenon, the human race doesn’t even register.

“We are pretty homocentric – is that a word?” Mitchell says, looking out the window to his garden. “I just carry on I guess, the garden is getting to be a metaphor for me. I take the long view. The Earth is going to endure.

“We’ve got, what, 5 billion people, a huge percentage of whom are not educated to these matters here in the United States which is supposedly educated. For Christ sake you have people who don’t believe in evolution, what is it, 41 percent of the population? What hope is there for such a people. And you can quote me on that.” Actually, it’s more than 7 billion people, including 42 percent of 318 million Americans who don’t believe in evolution, according to a 2015 Gallup poll.

Both sanctuary and observation post, his garden is where Mitchell watches our changing world unfold. He works strictly by hand, clearing, tending, pruning and shaping the thousands of ornamental plants he has planted at his property over more than 30 years. “The garden is a place, but it’s also a metaphor. It’s a sanctuary here for me.

“This takes work. I like the work. That is the main existential statement. It is hand work, I don’t use machines. I hate machines. I hate chain saws. I hate leaf blowers.”

Mitchell came to visit the Harvard Forest this week to speak at a conference, and so I took him out to meet the Witness Tree I am writing about. He put hand to its gnarly bark, tipped his head back to enjoy the canopy’s structure, asked about the life of the soil, the doings of the soldier beetles, did I know about them? For to Mitchell, everyone should know about everything in their little patch of the world around them. And for those who don’t pay attention to the great gyre of their small Scratch Flat, wherever it is, well. They are missing out.

“They are missing the scent of fresh cut hay, frog calls,” Mitchell said. “They are missing everything, 100,000 year’s of contact with nature, with the world, the real world. The arrival and departure of birds. I really don’t need a calendar any more, I am really conscious of the seasons. But it is changing, shifting, I have watched the gardens here for 30 years, and we used to get the first frost September 18 on the Equinox, a light frost, then we would get a killer on the 10th of October.

Looking up to the canopy of the Witness Tree. Just as John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest has seen the timing of seasons change at the Harvard Forest over the past 25 years of his observations, Mitchell notes later killing frosts in the fall, and on average, milder winters during his 30 years of observations at Scratch Flat.

“Now the light frost is in October and the killer is in November, and that is pretty standard for the last 15 years. We used to be a (USDA Plant Hardiness) Zone 4, now it’s 5 and we are pushing 6. I can grow plants here I couldn’t grow 20 years ago. I am growing a tree native to the Smoky Mountains. I should try crepe myrtle.”

And so as the great world spins, and another spring comes, Mitchell is back out in the garden, to work with his hand tools. “I love to scythe, you are on your own time, you want to listen to the birds, and with hand tools, you can hear them. I smell the grass, I just stop a lot and just stare into space.”

I listen, then have to ask him. For someone obviously so appreciative of nature’s wonder, what about climate change? Do we have the right to do what we are doing to the planet? He stops and thinks about that. Then answers me:

“If the animals could vote, they would say, we have no right. If they could put us on trial they would say we had no right to do what we did, that we are guilty.

“Do we have the right? Who’s to say, who is the judge on that. Right or wrong. I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to that, because the judges are the animals.”

Author John Hanson Mitchell at home in Littleton, MA, a.k.a. Scratch Flat, the landscape he memorialized in his book Ceremonial Time.

Leave a Reply