LYNDA’S BOOKS

Click on the cover above to learn more about each publication.

——————————————————————————————————-

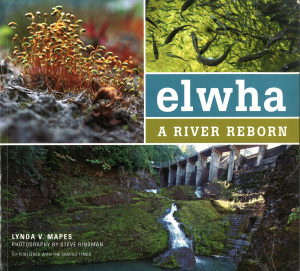

ELWHA A RIVER REBORN

The world’s largest dam removal project freed the mighty Elwha River of Washington State, opening 70 miles of salmon spawning habitat and revitalizing a legendary wilderness valley from the mountains to the sea. The last of the dams came out in the fall of 2014, in an unprecedented return to nature.

With more than 100 spectacular photos by Seattle Times photographer Steve Ringman.

—

REVIEWS

The Seattle Times

‘Elwha: A River Reborn’: The Resurrection of A River

By Tim McNulty

In “Elwha: A River Reborn,” Lynda V. Mapes and Steve Ringman document the process of restoring 70 miles of pristine salmon spawning habitat by removing dams on the Olympic Peninsula’s Elwha River. They appear Wednesday, May 8, at Seattle’s Mountaineers program center.

On Sept. 17, 2011, an excavator with a gold-painted bucket took the first bite out of the Elwha Dam. That marked the beginning of the largest dam removal in the world and an ambitious ecological restoration effort that will return salmon to Olympic National Park’s largest river system.

Beyond the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams lie 70 miles of pristine spawning habitat protected by the park, habitat blocked to salmon for a century. The Elwha River was legendary for its once-prodigious runs of all five species of Pacific salmon. By 2011 less than one percent remained.

The Elwha dams, built in 1913 and 1927, brought power and a degree of prosperity to the pioneering settlement of Port Angeles. But the Lower Elwha Klallam people, area fishermen, and a cherished national park bore the cost.

A new book by an award-winning writer and photographer team takes readers into the blue-green depths of the Elwha River’s story and nets an epic tale of natural and cultural renewal. In “Elwha: A River Reborn,” Seattle Times reporter Lynda Mapes and photographer Steve Ringman have done an exceptional job weaving together the many varied and often conflicting threads of the Elwha story. The pair spent more than two years accompanying scientists into the damp Olympic wilderness, conducting interviews and plumbing archives. Their reporting brings the Elwha’s long-awaited restoration brilliantly to life.

Drawing on excerpts from period newspapers, Mapes captures the tenor of the pioneering boom years, when developers like dam-builder Thomas Aldwell were able to shirk laws requiring fish passages on dams.

Mapes also sat with elders of the Elwha Klallam Tribe, including the late Adeline Smith, who as a child watched crowds of salmon splash past her parents’ farm house. “You couldn’t cross a stream without stepping on a fish,”she recalled. Smith and others recount how the Elwha people had no voice to protest when the dams were built. Indian people did not receive U.S. citizenship until 1924; the Elwha Tribe had no reservation until 1968.

But when the local pulp and paper mill applied to renew its license for the upper dam, the tribe led the effort to correct a decades-long injustice. In 1986 the tribe petitioned the federal licensing agency to remove both dams and restore historic salmon runs. The tribe was joined by four environmental organizations led by Rick Rutz, a scrappy scientist-activist who envisioned Elwha dam removal as a national issue.

“Not only do you not have to be an attorney,” Rutz told Mapes, “you don’t have to be a credentialed agency biologist to know a thing or two about this sort of thing, even when they tell you [you] are wrong.”

The Elwha River Ecosystem Restoration Act passed in 1992, but victory was short-lived. Local politics ensued. It would be nearly two decades before the dams were taken out — at a cost of $325 million.

“Why it took so long — and how a radical idea backed by a motley crew of Indians, tree huggers, and bird-watchers became a mainstream cause for the industrial establishment of Port Angeles — is one of the great stories of the Elwha,” Mapes writes.

It is a great story, well told and beautifully illustrated in fluid prose and striking images. As salmon swim past the former site of the lower dam, “Elwha: A River Reborn” celebrates a local environmental success story with planetary significance.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Elwha: The Olympics’ Greatest River Being Restored and Reborn

By Joel Connelly

The dams are coming off the master stream, the “crown jewel” of our Olympic Peninsula, with salmon and steelhead begining to return upstream to a vast, wild spawning habitat from which they were blocked for a century.

The rescue of the Elwha River is a bottoms-up, top down success story, driven by native American and conservation activists in one Washington, and enabled by a driving congressman and a former presidential candidate in Washington, D.C.

As Lynda Mapes writes in “Elwha: A River Reborn” (The Mountaineers Books, $29.95), “The Elwha has so much to catch up on: moving a hundred years worth of wood and gravel downstream: building and moving channels; conveying and nurturing the fish that feed a vast web of life along starved for nutrients from the sea.”

The new book, writen by Mapes and beautifully illustrated by Steve Ringman, is about more than just the recovery of endangered chinook salmon, in a place where nature will again run wild. (“We can’t just let nature run wild,” Alaska’s boomer Gov. Walter Hickel said a few years back.) It demonstrates a treasured, now-endangered tradition in American newspaper journalism.

Mapes and Ringman were allowed by their employer, The Seattle Times, to lay siege to a story. They teamed up not only to report but to understand the largest river restoration undertaken by the National Park Service in its 97-year history. The result is a richness of style and depth of detail, in a century-long saga that begins with exploitation and ends with redemption.

The Elwha is a 321-square-mile watershed, a “uniquely remote place” as Mapes writes. “Few other national parks in the country boast Olympic National Park’s isolation.” When not socked in, it even has the clearest night star vistas of the “lower 48” states.

Hundred-pound chinook salmon once spawned in the river, that is until a boomer Port Angeles entrepreneur named Thomas Aldwell caused the river to be blocked. A dam, and then another, were built illegally, with no fish passage, and with state collusion. As Mapes writes, “The hatchery soon failed, and the state gave up on the fish and walked away from the river.”

The recovery of the river was a dream of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. It gained monentum with Bruce Brown’s book “Mountain in the Clouds,” backing from U.S. Rep. Norm Dicks — who has fished for salmon out of Sekiu since he was a boy — and picked up an unusual ally in New Jersey Sen. Bill Bradley.

As could be expected, local wool hats mounted a save-our-dams campaign. The city of Port Angeles hit up the Park Service for a $30 million water treatment plant. The Farm Bureau threw a hissy fit that this would only encourage removal of dams from the Snake River. Luckily, the Japanese-owned pulp mill in Port Angeles chose to deal rather than demagogue.

Mapes has a fine eye for both natural ecosystems and inside politics.

She walks rivers with the chairwoman of the Klallam tribe, with biologists who explain life systems nurtured by salmon, and presents a sympathetic profile of the dams’ last manager. She gives us the nasty side of then-Sen. Slade Gorton, who resisted removal of the 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam.

“‘This is not going to be something I celebrate,” Gorton told Mapes. “And it is something in the past.” With that, he hung up the phone.

We do celebrate, and “Elwha: A River Reborn” is a substantial contribution to the Northwest’s natural and human history.

The Olympic Peninsula is not always well-treated by writers. The drippy, dreary climate has produced books with prose as thick as Devil’s Club. The Twilight trilogy boosted tourism in Forks, and produced movies that dominated this year’s worst-picture Razzie Awards. But their depiction as werewolves did a profound disservice to the Quileute Indians.

With Mapes book, however, immersion has produced prose as free flowing as the reborn Elwha. A few authors over the years — Mapes, Brown, Timothy Egan, and Ruth Kirk — have done justice to the place.

The book ends with chinook salmon swimming upstream past the now-removed Elwha Dam, and circling in a pool below the coming-down Glines Canyon Dam. As Mapes writes, “Theirs will be the last generation to confront this dam.”

Hopefully, Mapes’ will not be the last generation of newspaper scribes given the time and space to immerse themselves in such complex and wonderful stories.

TO PURCHASE

Please click here: Elwha a River Reborn

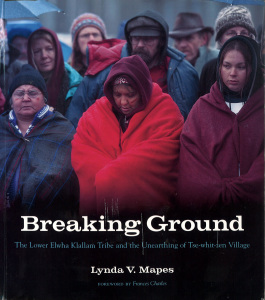

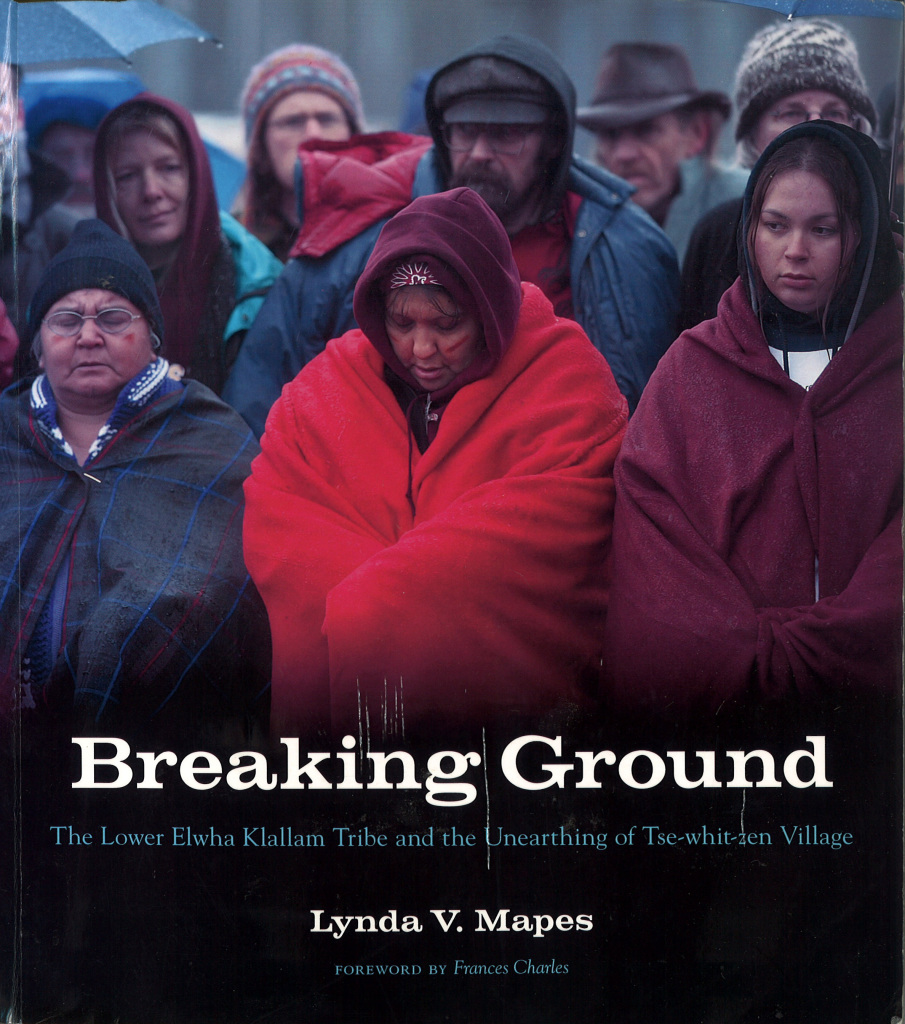

BREAKING GROUND

THE LOWER ELWHA KLALLAM TRIBE AND

UNEARTHING OF TSE-WHIT-ZEN VILLAGE

Heartbreaking and inspiring, this intimately reported story of the accidental unearthing of one of the largest, oldest Indian villages ever discovered in Washington State during a state construction project puts the contact experience between Indian and Europeans into its modern context, revealing the work still to be done on both sides to create a more whole and just society.

Richly illustrated with historic photos never before published, and documentary photography of the discovery of the site by Seattle Times photographer Steve Ringman.

—

REVIEWS

“A rich, compelling regional and environmental history combined with underlying public policy concerns made this narrative especially intriguing.”

-Oral History Review

“Her book thus provides a substantial and detailed record of the Tse-whit-zen dig and the community conflict and controversy involving the State of Washington’s Department of Transportation, the City of Port Angeles, and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. It is filled with details that are made more real by the fact that Mapes was a witness to many of the events she discusses and spoke firsthand with a number of key players. For these reasons Breaking Ground is an important record of the perils that confront individuals and communities in their efforts to collaborate across significant cultural divides.”

-Collaborative Anthropologies

“Breaking Ground is, by design, geared for the general reader, but its content is so valuable that it should be considered required reading for all, no matter the focus of one’s work.”

-The Midden

“Breaking Ground does a masterful job of telling this complex story, which is both an important part of Washington history and an object lesson in the perils of ignoring that history.”

-History Link

“A veteran journalist who writes well, Mapes relies on personal interviews for much of the story of the dry-dock controversy. Her obvious sympathy for the Klallam people gained her the trust of the tribal leadership and access to sources not available to the general public. . . . Breaking Ground makes a significant contribution to the continuing evolution of government’s often trouble relationship with American Indians and their tribal governments.”

-Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History

“After talking with so many players in this story-from the workers in the trenches to the leaders on both sides, Mapes shares a moving tale of a departure from ‘the way things have always been done’ to an approach that ultimately was more respectful, collaborative, and constructive. In our increasingly diverse society, it’s a good model to have.” -Kitsap Sun

“A fascinating, beautifully illustrated historical account that reaches as far back as 1790, when the Manuel Quimper expedition landed, and brings the reader forward to present-day native and non-native relations.”

-The Port Townsend Leader

TO PURCHASE

Please click here: Breaking Ground

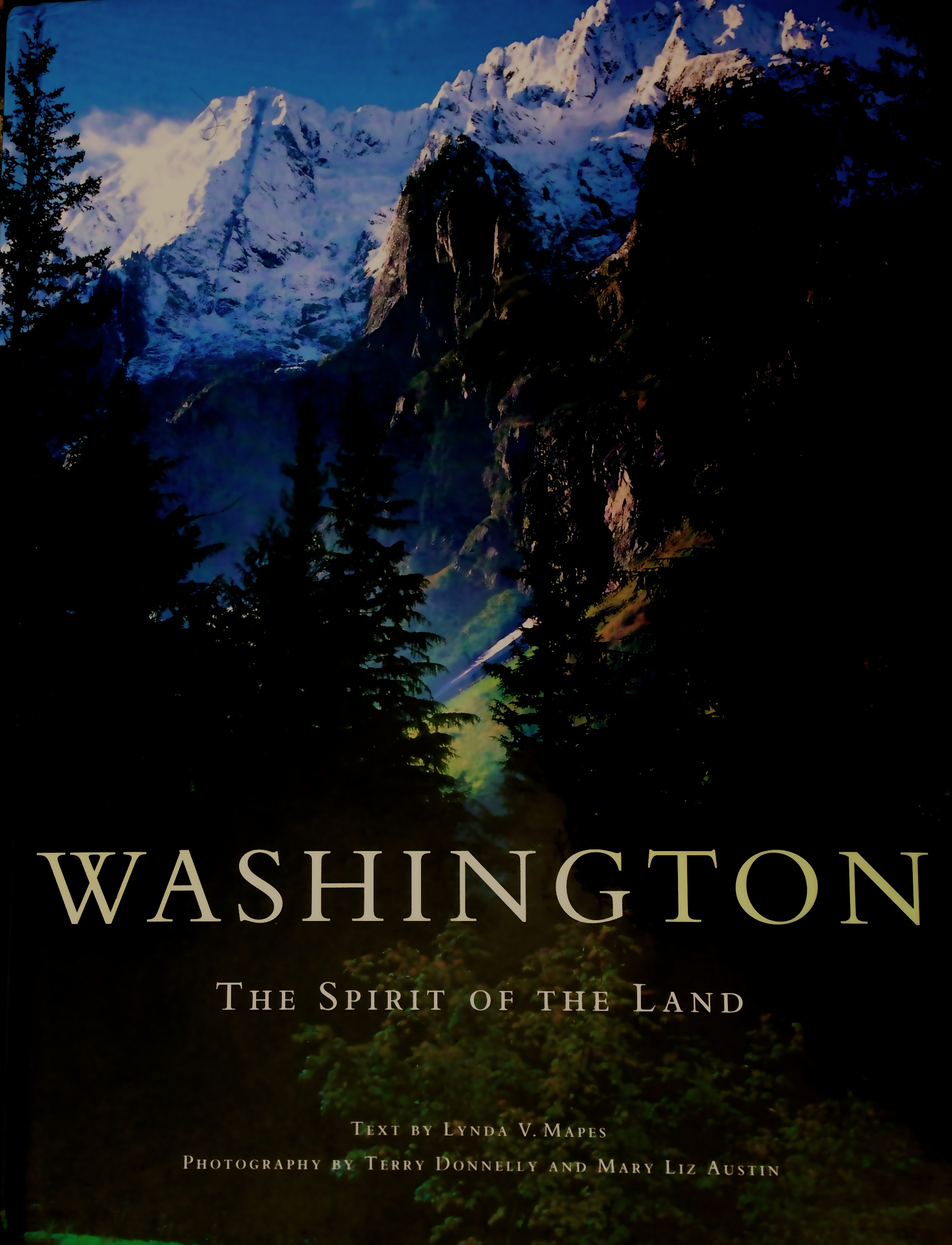

WASHINGTON THE SPIRIT OF THE LAND

Lavishly illustrated with large format photography by nature photographers Mary Liz Austin and Terry Donnelly paired with natural history essays by Seattle Times reporter Lynda V. Mapes, this is the book that showcases this jewel of the Pacific Northwest in its most grand and intimate aspects.

—

TO PURCHASE

Please click here: Washington: The Spirit of the Land