RIDING THE WIND

March 23, 2015

Like a boat tossing on waves, the big oak swayed in the wind, taking me with it. Dangling from my climbing rope and harness, way up here in the canopy, the big oak was making the rules, that’s for sure. A puny human way out of my terrestrial realm, no tree had ever given me a ride. But here I was, enjoying the rock of the big oak’s branches, something I had never felt before. It was a sea legs sensation I would keep on feeling for hours, even once back on the ground. But I was in no hurry to come down. No, not yet.

Since I first met this big red oak last year, I had been wanting to get here, some 60 feet up in its canopy. I just wanted to see what it was like, and to experience this bit of woods at the Harvard Forest from the tree’s point of view. I’m writing a book about how seasons are changing because of climate change – among other things – and it was time to get up here, and see what the buds were up to. Melissa and Bear LeVangie of Trees New England twin sisters and both professional, champion tree climbers, and two friends from the Knight program in Science Journalism at MIT, were game too. So up we went, with Melissa and Bear guiding our way.

I was worried about the wind when the day of this scheduled climb came. Forecast with gusts to 25 miles and hour, these March winds roar fiercely enough on the ground. What would it be like way up there? And it was cold, in the twenties. But Sunday morning arrived, and unlike even colder days when we had scheduled a climb, there was no last minute cancellation, for safety’s sake. So I rousted Dusty, my cat, and hurried out of bed to put the coffee on, and heat up the cast iron skillet for pancakes.

The first day of spring had come and gone, but I layered on the clothes. Wool long underwear. Snow pants. My big boots with the wool liner. Hand warmers to tuck in my mittens, and a Thermos of bracing black coffee.

At 9 am sharp, everyone arrived in high spirits. We loaded up the camera and climbing gear and drove up to the Barn Tower at the Harvard Forest, then packed our stuff into the woods. The tree — BT QURU 03 — was waiting.

The name comes from the red oak’s identification tag, stamped on a round metal disk hung from its trunk by a twisted wire on a nail. The tree is a tagged, tracked specimen – a living scientific instrument – in a long-term study of how tree phenology – or seasonal change – is being altered by climate change. The tree is named for its location at the Barn Tower (BT), its species (QR for Quercus rubra, red oak) and the year it was accessioned into an ongoing tree survey by Harvard Forest field phenologist John O’Keefe. I picked this tree to study with John’s help last year for a book I am writing, while living here at the Forest as a Bullard fellow in forest research. Witness Tree, under contract with Bloomsbury Publishing, explores the story of this 100-year old oak as a living timeline of our changing relationship with nature — and its consequences.

To get to know this tree, I knew I would want to climb it. I’d done a practice climb on it once before with Melissa last October, but didn’t get up very high. Then came a practice climb with Melissa and Bear, and Patrick Wellever, digital media training coordinator at the Knight Program in Science Journalism at MIT, and KSJ fellow Rachael Buchanan, a producer from London at the BBC. We climbed a much smaller black walnut tree last November in the front yard of Community House, where I live at the Harvard Forest, for practice. Now, after several cancellations and weather delays, we were finally ready for our ascent into the big oak.

We started by heaving a throw bag up into the tree to set our climbing lines. Harder than it sounds in so big a tree, it took me probably twenty tries to wing the bag up into the first rank of branches, bringing the line with it. “Commit to your throw!” Melissa kept saying, urging me time and again to use a freer, swinging motion to release it high into the blueness of the sky. With our lines finally set, it was time for lift off.

With a blur of buckling and clipping, we got into our harnesses and sat for the first time on our climbing lines, our feet swinging free a few feet off the ground. Like a kid in a swing set, I felt a pure glee.

Lift off. Patrick Wellever is liking this first moment of his feet off the ground as we get ready to climb.

Climbing is my favorite part of this. With the right gear, superb instruction with a solid safety ethic, and good mental focus, climbing even a big tree like this red oak can feel natural as walking. I pushed my leg into an ascender Melissa set on my foot to give me power and lift, and pushed the friction hitch up the rope as I ascended the line, sure and smooth. How fast I could go, and how high! It was hard physical work, no question. But what a thrill, to be up here! Everything on the ground – our blue tarps with gear, the understory trees I had come to know so well – they were suddenly far below.

I had a bosun’s chair set in my harness, and enjoyed just leaning back for the view. How much life there was on every inch of these branches! Moss and lichen packed along the rough hide of the oak’s bark. I could see so much better up here, nested in the tree’s branches, how the structure of its canopy opens to the sky. Each branch was positioned to gather the sun, every twig claimed its space.

It had been a long, cold winter, and while it was March 22, some 60 feet down, the snow was brilliant white and still deep on the ground. The sky has that radiantly clear, deep- blue depth of winter, when the air is too cold to hold much moisture. There was no pollen in the air yet either, that’s for sure, without so much as a pussy willow catkin open yet. The oak’s branches were studded with buds still clenched tight.

Another gust gave the tree a big push. “You never get used to it, because it’s always different,” Bear said from across the trunk, as it leaned.

Rachael takes a group photo from the very top of BT QURU 03. That’s Melissa in green, Patrick in black, me with the wool scarf, and Bear in red.

I looked into the forest, enjoying my view into secret worlds invisible from the ground. I saw woodpecker holes drilled way up into snags. I could see much more distinctly the complex weave of the canopy, each tree growing just to the edges of the next. But I didn’t see any birds in the oak, or nests. That could change as the season progresses. “In spring the chickadees come visit you,” Bear said. “They are so social, and not at all afraid. Sometimes we come across mourning dove nests tucked in the crotches of branches.”

Tree climbing is a gear intensive undertaking. Melissa and Bear provided the instruction and gear to make it fun…. and safe.

Next month, we plan to climb the tree again, and I know I’ll be hoping for birds. We also have a notion to bring lunches up here, for a treetop picnic. We saw just the perfect spot.

But for now, at least for me just being up here was thrill enough, enjoying the big oak’s ride in the wind.

NEW SEASON, OLD WEATHER

March 21, 2015

Ah the first day of spring: 22 degrees, and snowing. Should have known! Today marks a brand new season, but here at the Harvard Forest, it’s the same old weather. The winter of 2014-15 has already gone down in the history books here in New England as one of the coldest and snowiest ever. Boston broke its all-time snow record, with 108 inches. All the nuttier for me, living here at the Harvard Forest away from my home in Seattle – where my husband Doug keeps sending emails of flowers and blooming trees and crowing about already cutting the grass. Seattle shattered records for the warmest winter on record while we froze.

As I wrote in my last post, these are the sorts of extremes that we can expect to be our new normal as global change shakes up our world. Phenology – the study of seasonal changes in nature – has become a study of how we’ve altered seasonal time itself. The primary cause is people burning fossil fuels, which insulates the planet with heat-trapping carbon dioxide gas. Carbon dioxide levels are higher in the atmosphere now than they have been as far back as we can see, in gas bubbles trapped in ice from 800,000 years ago. As we keep stoking the climate system with more heat energy, expect more extremes to come; we’ll never settle down to whatever we thought normal used to be. Here at the Harvard Forest, while this winter was one of the coldest and snowiest, the winter of 2011-12 was one of the warmest.

But it was the first day of spring, so I went out for a walk to see what signs of the new season I could find. For one, I wanted to visit Joshua Rapp, a researcher at UC Davis working at the Harvard Forest. He fired up the boiler in the sugar shack today for the first time this winter. Rapp said he tapped trees on March 9 — about three weeks later than usual. But it wasn’t until last week that the snow finally drew back from the roots of the sugar and red maples, letting the sun into the tree wells in the snow and warming the soil at the roots. Finally, the sap started to flow, and the trees’ frozen crowns thawed.

Researcher Joshua Rapp started boiling sap today from the maples he tapped March 9 — about three weeks later than usual because it has been so cold.

The sap tapped in sugaring isn’t so much coming up from the ground, as flowing down from the thawing crown of the trees when daytime temperatures climb above freezing. Warm days and cold nights really get the sap flowing. But mostly, it’s just been… cold.

Snow drifted past the windows as the maple sap boiled over the wood fire, and the soft sounds of crackling wood and roiling sap purred in the cozy shack. An old pool house, the sugar shack was renovated by the Harvard Forest Woods Crew. This is its second season. It’s a beautiful building, classic and simple, sitting on a little rise at the edge of the forest overlooking meadows and stonewalls.

Rapp had a bit of finished syrup already. It was a beautiful, clear red-amber color. And the taste! Its maple essence bloomed on the tongue like a fine wine. He hopes to make 20 gallons this year.

Rapp is making this syrup from 29 tapped trees at the Harvard Forest – 19 sugar maples, and 10 red maples as part of his work studying the masting cycles of trees and its relationship to syrup production, and research he’ll continue on the maple syrup industry and forests as a Bullard Fellow, working in collaboration with Harvard Forest senior ecologist Johnathan Thompson come September.

Sugaring is patient work, watching the sap closely to make sure it doesn’t burn, and pouring it off at the right concentration. The trees have to cooperate too, and so far that’s been dicey. The sap collecting bags hanging on the sugar maples that line the Prospect Hill Road here at the Harvard Forest seemed a sign of spring for sure until a close look revealed the sap was frozen solid in the bags.

What’s wrong with this picture: The sugar maple sap froze solid in the bags on the first day of spring.

No surprise, really. It was cold enough to keep piling on my double wool mackinaw and I didn’t need snowshoes because the foot and a half of so of snow had freshly crusted with ice.

I said good-bye to Josh after that delicious taste of syrup and went up to check on BT QURU 03, the big oak I am writing a book about here as a Bullard Fellow. The oak has seen about a 100 winters, and was wearing a fresh dusting of snow when I stopped by.

It may well be two months before I see the first leaves on BT QURU 03, the grand old oak I am studying. It wore a fresh dusting of snow today.

I looked hard but saw no signs of spring at all yet in the forest, not so much as a pussy willow catkin. True, the birds are more active, but it had just started snowing again, so they were hushed. The longer daylight though was still a gift of the calendar. Now that we have passed the equinox, the days will now begin lengthening even more rapidly until the summer solstice in June.

I cut a bouquet of twigs from a half dozen varieties of native trees to bring indoors to force, so I can watch the buds unfurl up close. After all, at this rate it could be another two months before I see the first leaves on the big oak. For now, the twigs will just have to do.

With few signs of spring in evidence, I cut twigs to force inside. These will be the first leaves I expect to see for quite a while.

EXTREME IS OUR NEW NORMAL IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CHANGE

March 2, 2015

Here in the wintry Northeast, cities are shattering records for the snowiest and coldest ever. Boston called out the National Guard last month to shovel out the T, and the National Weather Service office in Taunton, MA reported on Sunday that February was the all-time snowiest February ever in Boston since 1872, with a record 64.8 inches, burying the record set at 41.6 inches in 2003. Boston also beat its all-time record of any snowiest month of 43.3 inches set in January 2005. Seasonal snowfall was also a record, at 99.4 inches, beating 81.5 inches set in the winter of 1993-1994. February was also the second coldest, with a monthly average of just 19 degrees. So it goes all over the Northeast, where this winter temperatures have been tumbling to record lows and snow has been piling up to record highs. Transit workers are bashing ice out of the tunnels in New York and here at the Harvard Forest, in Central Massachusetts, I don’t know why they ever put the snow blower away.

There’s three feet or so of snow out my window here and more on the way. I went out for a snowshoe this morning to enjoy the animal tracks on fresh snow that fell overnight. The first day of spring is March 20, but it sure seems a long way away.

Deer mouse tracks in fresh snow this morning here at the Harvard Forest. We had a couple more inches of snow overnight and more is forecast. Perhaps the mouse was after a cache of food, or diving into a tunnel it maintains under the snow.

Meanwhile, my home town of Seattle is the mirror image of Boston in more than the Superbowl. While we are piling up snow records here, Seattle has just recorded a record warm winter. There is so little snow, the ski resorts have choked and there’s serious concern about winter snowpack — our source of surface water and nearly 90 percent of the power supply for Seattle City Light. Good luck with that this year: my husband Doug all last month was emailing me photos of daffodils, crocus, and daphne in bloom weeks ahead of schedule. The star magnolia is in full glory, and the evergreen clematis, too. On Sunday, he cut the grass. Really!

While I shovel the walk at the Harvard Forest, Doug is cutting the grass in Seattle. We are seeing record cold and snow while Seattle basks in a record warm winter. Snowpack in some Northwest mountain ranges is at 17 percent of average. Extremes and anomalies are our new normal in the era of global change.

My friend Jonathan Martin on the Seattle Times editorial board wrote an ode to winter published today, pleading the snow gods to return.

Things could still change, he rightly points out. I still remember the press conference in which then Gov. Gary Locke declared the state to be in a drought in March, 2001. A deluge of snow and rain in the lowlands arrived within days, and the water year ended up just about average.

Climate change deniers will surely seize on the ice box of this winter in the Northeast. But the true, long term story of our warming climate is beyond dispute.

Last year was the hottest on Earth since record keeping began in 1880, surpassing 2010 as the previously warmest year. The ten warmest years ever have all occurred since 1997, if you are counting.

Maybe if as scientists do we all called what we are witnessing “global change” rather than “global warming,” this would all make more sense, or at least be less of a predictable laugh line. Because it is change that we are living. Not warming everywhere…but change. At a rate that is smoking hot.

Aaron Ellison, a senior ecologist at the Harvard Forest, points out the sorts of extremes we are experiencing is exactly what we should be expecting. “Every day, it’s another anomaly,” he says. “This is what systems do, when they reach a tipping point.”

A wholesale reset is nothing new for our Earth, whose climate is not terribly stable. Twenty thousand years ago, Seattle, Boston and New York were under a mile of ice. In just the last 12,000 years, sea levels have risen 400 feet, with the melting of all that ice. That’s a blink of an eye, geologically speaking. Go back 650 to 750 million years, and there’s evidence Earth was a giant snowball, one big ball of ice. And earlier, as dinosaurs walked the Earth, our planet was ice free, all the way to the poles. Since modern humans arrived, about 200,000 years ago, we’ve lived in a relatively stable, friendly climate between reigns of ice, the most recent ice age ending 12,000 to 15,000 years ago. Because it’s what we know, we think this climate that we are used to is what life on Earth looks like. But it wasn’t, much of the time, looking into the past, and surely, at the rate we are going, it won’t be in the future.

Human-caused climate change is not controversial among climate scientists; it is a predictable fact, and really, a matter of simple math. Svante Arrhenius, the Swedish physicist (1859-1927) discovered the greenhouse effect, and understood that if we doubled CO2 in the atmosphere, it would increase surface temperatures by 4 degrees, and if we increased it fourfold, the temperature would rise by 8 degrees. That was in 1906. Notes Kerry Emanuel, the climate expert at MIT, “With a piece of paper and a pencil he gets to nearly the same place as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its 2013 estimates.” Impressive, true, but not really surprising for a guy good at figures. Global warming is, after all, at its simplest, a matter of adding more carbon into the atmosphere than the standing stock of plants in the living biosphere, both on land, and in the planet’s waters, can absorb.

It’s not the absolute number of parts per million of C02 in the atmosphere that matters; it varies from season to season, and year to year anyway. It is the rate of change over time that counts. The amount of C02 in the atmosphere today is higher than it has been in the last 800,000 years, and probably higher than it has been in the past 20 million years. Think of it this way: We have caused the CO2 content in the atmosphere to rise as much since the big oak sprouted as it rose over 8,000 years during the transition from the last ice age to the current interglacial period. Such a fast rate of change in the chemistry of the atmosphere is probably without precedent in Earth’s recent history, putting us in what geologists call a no-analog world. And we have a lot more fossil fuel left to burn, if we choose to. Work at it, and we could stoke temperatures right back to the dinosaur days of the Cretaceous.

Global warming, climate change, these are useless terms really, that fail to communicate what is really happening: The problem isn’t just that we have warmed the atmosphere. It is that we have created an entirely new system, with feedbacks of its own. The temperature of the air, the winds, the mixing of ocean currents, and chemistry of the seas, food chains, the migrations and interactions of plants and animals and their home ranges — they are all connected. Change any part as fast as we have, and all the rest will cascade into new interactions that are already changing things for us, and many other beings with whom we share the planet. Meanwhile C02 levels will go beyond doubling and by the end of the century, most experts think, and probably triple.

THE GLOBAL IS LOCAL: THE CLIMATE IS CHANGING AND WITH IT, OUR SEASONS

February 27, 2015

Scientists will tell you the climate is changing. So will John Latimer.

A postman in Grand Rapids, Latimer recorded the changing seasons in nature as he drove his 100-mile route for 30 years in rural Minnesota. Latimer said he started keeping records of what he saw and heard around him on his route as the seasons unfolded just to keep life interesting. When did the lady slippers bloom, the trees bud out, the frogs start calling? He wrote it all down. Latimer said his patrons soon learned if they saw his car off by the side of the road, their mail might be a tad late: “My patrons were very forgiving, my car would be off in a ditch, I’d be off looking at some plant.”

John Latimer, left, with Miriam Johnston of the Richardson Lab and John O’Keefe, Harvard Forest field phenologist, enjoying a winter walk at the Harvard Forest on a recent visit. They are collaborating on research that uses observations of seasonal rhythms of nature to document climate change.

Latimer became so bitten by the phenology bug, he even started a radio program on radio station KAXE in Grand Rapids about phenology – the formal name for looking and listening for seasonal changes in nature, and keeping a record of observations over time. Latimer’s phenology program is the most popular show in his market. The station also hosts Latimer’s list of events to watch for in nature every month on its home page. Whether it’s pussy willow catkins emerging and bald eagles returning to nests in March, or the songs of wood frogs, dandelions putting up first flowers and painted turtles emerging from hibernation in April, Latimer invites people to tune into the wonder of life all around us, and take note of the grand pageant of nature’s seasonal rhythms. He’s posting right now about the first sights and sounds of spring to more than 300 followers on Twitter, and has a Season Watch Facebook Group page, where people put up their own photos and observations.

That’s new technology for a very old practice. Some of the earliest phenological records are thought to be those of crop yields in ancient China in about 974 BC. In Japan, written records of annual peak flowering times of cherry blossoms have been maintained for more than 1200 years.

Now climate change has brought a resurgence of interest in phenology. The seasons aren’t what they used to be. People see and sense what nature is telling us: while every year is different, on average, over the past two decades spring is coming earlier, fall later, and winter is getting squeezed on both ends. And that has consequences for living things of just about every sort, and their environment.

Latimer, left, and O’Keefe share an infectious enthusiasm for understanding the workings of the natural world.

The link between observable changes in seasonal rhythms of nature and climate change is also giving phenology new relevance for climate change researchers. Andrew Richardson, associate professor at Harvard University, has been using a 25-year record of tree phenology compiled at the Harvard Forest by field phenologist John O’Keefe in his climate change work.

O’Keefe’s observations of the same 40 tracked trees in spring and 50 in fall comprise the best phenological record known anywhere of woody species, for the quality and consistency of his observations, the number of species he watches, and availability of his work for researchers. His data is frequently used by researchers investigating the effects of climate change on forest ecosystems.

Phenology research at the Harvard Forest shows those connections, in ground-level, observable effects from earlier spring bud break to later frost, keeping the leaves on the trees deep into fall. “It’s a way of knowing what the plants are doing,” O’Keefe said. “We need those plant-level observations to know what is actually happening.”

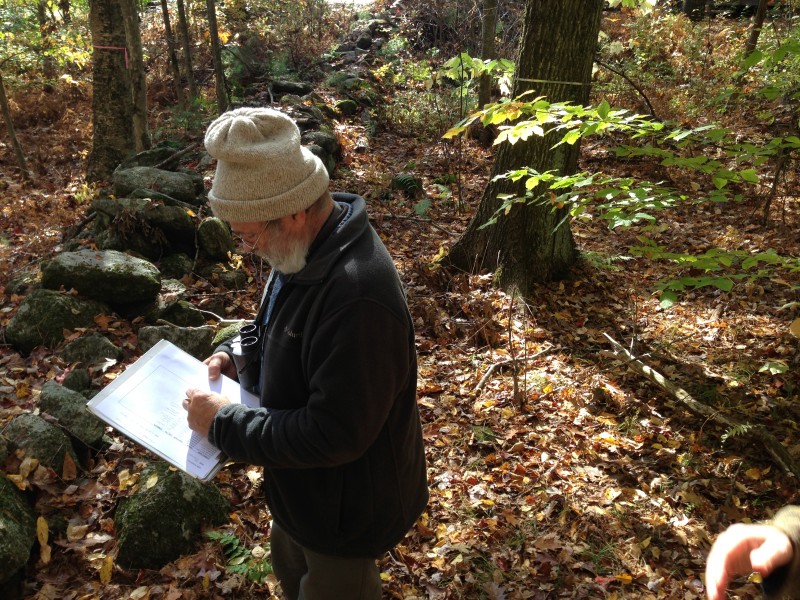

O’Keefe, right, will begin his 26th year of phenology observations in the Harvard Forest this spring, in collaboration with the Richardson Lab at Harvard University.

Now the Richardson Lab is bringing a similar approach to a new venue, using Latimer’s data. Graduate student Miriam Johnston in the Richardson Lab has taken on the project of incorporating Latimer’s data in the lab’s new project, improving models predicting phenological responses to global climate change at the USDA Marcell Experimental Forest in Northern Minnesota. In addition to their work at the Harvard Forest, the lab is developing forecasts of how peatland phenology will respond to climate change over the next 50 to 100 years.

Foot for foot, peatlands pack away more carbon than any other land ecosystem – more than tropical rainforests, more than grasslands, more than woodlands of the Northeast or old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. Three percent of the Earth’s land surface is in peat bogs, Johnston noted, and they hold the equivalent of about half the amount of carbon in the atmosphere as C02 today. If peatlands degrade, they could release their carbon, worsening our climate change woes. “So it is good to know what is happening there,” Johnston said.

Miriam Johnston of the Richardson Lab is working with Latimer to incorporate his data into the lab’s work improving computer models of climate change.

Latimer and O’Keefe have each seen big changes in the environments they observe over the years. It was not uncommon to have a hard frost anytime from mid-September, even early September, O’Keefe said. “Now it can be mid and even late October.” Latimer, meanwhile, said he has watched the growing season extend by about a month in Minnesota. He’s found out the hard way that ponds he used to confidently skate don’t freeze like they used to.

No wonder. Globally, last year was the hottest since record keeping began in the 1880s, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, with the increase in global average temperature closely tracking rising levels of atmospheric C02. Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere are the highest they have been in at least 800,000 years, rocketing to more than 400 ppm C02 and climbing in just the past 150 years. This change in the air has direct effects on physical and ecological systems on the ground – because of course they are connected.

Phenology is helpful to science, but it is also just a wonderful way to connect to the natural world. “You become intimately conscious of what is out there,” Latimer said of his phenology walks. “What am I going to see today, what wonderful thing will happen?” Latimer recently retired from his mail route, but he’s keeping up his radio show and still checks up on parts of his route. The lady slippers, for instance, draw him back. “They were my pets for 20 years I was waiting for when they would come up out of the ground.

In addition to being useful to science, phenology is also a wonderful way to connect with the natural world. O’Keefe explains the workings of hobblebush, a native species without covering on its buds.

“When you go out to check on some plants it’s like checking on your kids,” Latimer said. O’Keefe says of his trees: “For the most part they are all good friends.”

Beyond phenology, the two also share a path of serendipity. Neither started off in the sciences, but found their way to phenology as their career paths unfolded. A sociology major at Harvard, O’Keefe said he was always interested in science. After a stint in the Peace Corps and the Massachusetts Air National Guard, he decided he wanted to learn what was going on in all that forest he was flying over, piloting an F-106. He went on to earn a PhD in forest biology, and work at the Harvard Forest, as director of the Fisher Museum. O’Keefe initiated his phenology walks while working at the forest, and has continued them in his emeritus position in retirement. He’ll begin his 26th year of walks in collaboration with the Richardson Lab this spring.

For his part, Latimer says he never expected to be a postman. But when he bailed on his training as an economist, he never looked back. “One day I just looked out the window and thought, ‘God I wish I was outside.’”

Neither O’Keefe,right, or Latimer, started out in the sciences but the joy of discovery drew them in to their study of the natural world through phenology.

WOOD FROG WINTER

February 17, 2015

This morning it was 8 degrees when I got up, and that was a big warming trend, 16 degrees toastier than when I turned in. It is a wonder to me that the tender, tiny animals of the forest survive when the temperatures plummet like this, and the snow piles up.

The animal that bring us our earliest spring song amazes me the most: The common wood frog. I marvel at this small animal, not as big as my palm, that looks so delicate and finely made. Yet it is incredibly hardy. In winter, wood frogs hibernate close to the ground’s surface, snugged into the soil and leaf litter. By now, in mid-winter, they are the living dead of the forest. They actually freeze, just about solid. Yet the wood frog survives. As winter comes on, they shut down their life functions, and hunker in their hibernaculum, to tough it out until spring. Even while frozen to a frogberg, glucose in the wood frog’s tissues works like anti-freeze, protecting its vital organs. When the ponds first start to thaw, so do the wood frogs. They are ready to go first thing, all set to mate and start a new cycle of life. …READ MORE…

WITNESS TREE BOOK TALK THIS WEDNESDAY

February 6, 2015

I’m excited about my first public book talk on my Witness Tree project his week. On Wednesday the Harvard Forest and the Athol Bird and Nature Club are hosting a presentation at the beautiful, classic Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, MA. We’ll probably broadcast the talk live on the Web, too, stay tuned for an update on that. I hope my collaborators at the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT, the Harvard Forest and the Richardson Lab at Harvard University will make it out for the talk. I know for sure lots of nature aficionados from the local community will be there…I have been so impressed by the dedicated and enthusiastic community of naturalists here in the Petersham and Athol community and environs.

Up in the trees in the Harvard Forest with the Richardson Lab. Andrew Richardson, associate professor Harvard University, left, and Morgan Furze, PhD student, right.

I will show lots of slides of the trees, native plants, and animals I have come to know here in the Harvard Forest, and some of my work with collaborators reporting my book Witness Tree, under contract with Bloomsbury Publishing. I’ve been at work on the book here since moving in at the Harvard Forest last September as a Bullard Fellow in forest research. The book takes a deep long look at the history of one tree here at the forest — a beautiful, 100-year old red oak, to tell the story of our twined human and natural histories, and changing relationship with nature. I’m focusing in particular on phenology, the practice of observing seasonal changes in nature.

John O’Keefe, field phonologist at the Harvard Forest, recording the seasonal progression of BT QURU 03, the red oak I am observing for my book, Witness Tree.

By watching nature — especially the seasonal progression of the tree canopy — we can see the workings of the ecology of the forest, and how they are changing because of climate change. I’ll talk more about this on Wednesday. Meanwhile…the snow here has been spectacular, we’ve had more than a foot of pure sparkling white and the lengthening days of February and clear blue skies and sunny afternoons have made for delicious explorations in the woods.

My tracks from a sunset snowshoe yesterday. The weather has been exquisite for a snow-starved Seattleite.

The writing is going well, I’m about finished with chapter six (of ten in the book.) So there will be plenty to talk about Wednesday! Thanks to the forest and the Athol Bird and Nature Club for sponsoring. And an early valentine to Emery Boose, special investigator and information manager at the Harvard Forest for getting the Witness Tree cam up and running today after a hiatus when the cable failed. We’re back to posting beautiful live images of the Witness Tree on the Harvard Forest web site, along with other web cams in the forest, 365 days a year during daylight hours. Enjoy…it’s a beautiful tree. Thanks to the KSJ program, which purchased the camera, and to the Harvard Forest for all the technical support. It will be great fun to watch these images change daily as the big oak’s leaves start to come out.

The Witness Tree, beautifully captured on the Web cam. Live images are beamed to the Harvard Forest home page. Watch the tree go through its seasonal year.

Winter from the windowsill

January 31, 2015

Just some photos this morning, to take you into my world of flowers and frost.

It’s roaring with wind outside this morning, but snug in my sunporch, aglitter with frost on the windows

Jasmine is one of the loveliest choices for an indoor garden. The cool, bright sunporch is just perfect for it. This plant has been showering me with flowers since before Thanksgiving and is still going strong. It’s my first time growing it and I don’t think I’ll choose to ever live without one.

My indoor garden is abloom with hyacinth, paperwhites, and winter jasmine. The fragrance and white flowers inside are the perfect foil to the frost and snow outside.

The frost creates portals into secret worlds. Here is where I sit under the black walnut, enjoy fires with friends and write at the picnic table. Well, not now. But later when the nine inches of snow (More? I lose track) are gone.

Sun through frost has an otherworldly, almost underwater look, which, I suppose, is just what it is.

The simple pleasure of paperwhites…all pristine prettiness and perfume. And in a cool place, they last and last and last. These first bloomed before Christmas.

Hemlock Dreams

January 25, 2015

The lure of a favorite hemlock grove drew me out today, to see the trees wearing yesterday’s big snow. And who could stay in on such a radiant winter day, with its bluebird sky and sunlit, glittering facets of pure snow and ice?

Not me, not a chance, so off I went to the Rutland Brook Wildlife Sanctuary near Petersham, a paradise of a trail meticulously maintained by Mass Audubon. The trail was drifted deeply with snow, but no matter, with those blue medallions nailed six feet up on the trunks of trees marking the outgoing trail, and yellow on the return. I bushwhacked through the snow, quite alone, enjoying the deep quiet of the winter wood.

Heading to Porcupine Ledge, I walked first along the Rutland Brook, so deeply frozen that much of it murmured out of sight under the ice. But there were places where its momentum broke free, and the icicles it splashed onto snowcapped rocks glinted with sun.

Then in a hush and long shadows, suddenly there they were: the hemlocks, in all their stately grandeur. I wanted to see them today in particular, to enjoy the snow thrown in sparkles from their wind-tossed boughs, and the backlit ferny green of their branches.

These hemlocks are monarchs of this winter wood, a gallery of elders, arrayed all in a line along the brook, in rank upon rank of big trees. Chickadees were probing their tiny cones for seeds — and both the cones and the birds seemed smaller than ever amid such big trees.

I turned up the Ridge Trail, taking my walk further into the woods. Light spilled across the hills and the hemlocks painted long blue shadows across the snow.

Porcupine Ledge, when I reached it, was basking in late afternoon sun, jagged icicles glinting from its top-most ridge. If there were porcupines in there, they were snugged deep in the rock for a long winter’s night.

It was time to head back. The bright sun was at a deeper slant now, as the afternoon came to its close. Soon I was back on the trail along the brook, winding through the big hemlocks, many too large to surround with my arms.

This forest looks healthy, it’s hard to imagine it without these trees someday. But I suppose that will one day be so, with the advance of wooly adelgid, an invasive pest killing hemlocks by degrees in the New England woods. Perhaps the consciousness in so many people over so many years walking this footpath will keep their memory alive. A hemlock dream so many of us shared in deep winter.

Inside the Snow Globe of Winter

January 17, 2015

Snow drifting under the door and north facing windowsills this morning were my first clues that today would be like none other so far this winter.

The powerful storm sweeping over New England didn’t get started at the Harvard Forest until the wee hours. When I went to bed at midnight I was disappointed nothing much was happening.

That all changed by this morning. When I first opened my eyes, there was something odd: the windows were…white.

The white out at my windows was quickly explained by the sound of the wind, roaring through the trees, blowing curtains of snow through the air. There was so much wind blowing so much snow, it was hard to tell what was falling from the sky, and what was just swirling around.

I rousted the cat and we both padded downstairs to see what was happening outside. Out front, in the pasture, it was hard to tell how deep the snow was, the drifts were so uneven. That’s when I saw the snow on the doormat inside the door, and on the insides of the windowsills and thought, so: This is what a blizzard looks like. I layered up to go out, and headed into the woods.

It was still snowing hard. The flakes cruised across the pasture in great billowing sheets, like the filled sails of a tempest-tossed brig. The snow was so fluffy the snowshoes weren’t much help; I sank to my ankles, the snow poofing over my feet like whipped topping. I marched on, knees pumping high, to make progress into the drifts. I wanted to go see the big oak.

I found it robed in softness, its trunk sheltering hidey-holes between its thick roots. I wondered what lives might be slumbering in there, under the snow, and even tunneled deep in hibernacula underground. Some animals, such as frogs, will actually freeze solid deep in the duff, reviving from their torpor come spring.

I thought about all the lives slumbering under the snow, and in the cleft bark and roots and hidey holes of the big oak.

But up here, out in the snow, I saw no animal tracks anywhere, and heard no birds at all; the storm was still too active for any animals but a curious human to be out and about. So I lay back in the softness, to just enjoy looking up into the oak, watching the snow sift and drift through its broad, reaching canopy.

The forest sounded different today. There were more creaks and groans and cracks from the trees. Not because of cold, it was 18 degrees, so it wasn’t the temperature. No. It was the wind.

Big gusts kept rocking the trees; the snow was not settling on their swaying branches. It’s one reason the forest didn’t reveal the foot or so of snow already fallen: the trees were swept bare by the wind.

Yet how peaceful it was deep in the woods, with the trees taking the brunt of the wind. I walked on, the feathery snow inviting a sliding gait. I was boating, really, the snow combing in breaking waves off the prow of my snowshoes.

The wind was wild, but the tree tops took the brunt of the gusts. Deep in the woods, these tree ears were stacked deep with snow, even though the upper branches of trees were blown bare.

The offices as the forest were shut down by the weather, but the Woods Crew was hard at it all the same, valiantly clearing the parking lot and wagon roads. “Cleaning,” they call it, and it denotes their relationship to snow, working to keep the rest of us all snug and safe. Harvard University is shut down today, but not the trails at the Harvard Forest. They are open 365 days a year, for free, thanks to the Woods Crew, keeping the parking and trail access roads clear.

By late afternoon, the snow was still coming. And I thought, watching it swirl, how very grand to be here, inside the snow globe of winter.