IN THE PALACE OF WINTER

January 8, 2015

The snow is blue-white, and the sky a long, clear view into infinity as I wait for morning’s full light. The black walnut tree outside my kitchen window stands in spidery silhouette, its symmetry a fugue of refrain and repeat.

To the west, the board fence stitches the white snow of the pasture at the Harvard Forest, empty now. We gathered the last of the cows yesterday in a rumpus of a wrangle, five men, two packs of hamburger rolls — and me, singing “Deario, Cheerio,” to the two stragglers left of the herd. We all decided that my afternoon treats for the cows of English muffins and molasses made them reluctant to leave. But at last, they loaded into the livestock trailer, just in time, too, before the coldest night yet of the winter set in.

This morning the iPhone reported -8 when I awoke, and the kitchen was 58 degrees. I cranked up the oven to bake some muffins, and settled by the window to wait for sunrise. The night’s moon, mostly full, still sailed in the east, but the brightening rim of the bowl of the sky was feathered with the tips of the trees. Each branch and twiglet showed in sharp definition and the brushwork of the white pine was delicately etched against the sky.

I looked to the upper pasture, where the sun always comes first, but no, not yet. The gold that spills from the top of the hill on down was still hoarded in the night.

On the porch, the windows were too thick with ice and frost to see out, but for a few melted peepholes to the pasture and woods. The scent of paper whites and white jasmine I keep out there for the coolness was thick and sweet.

I thought of Sarah Luce Mann, the housewife whose diary from 1861, kept in the Harvard Forest Archives, I am reading. Living a stone’s throw from me 154 years ago, did she relish this secret, quiet, waiting-for-the light-time, looking at these same views of pastures and woods? Or was she already at work? Probably: in her diary, every minute of her life is a verb. Washed, scrubbed, churned, knitted, mopped, ironed, sewed, carried. And her all-purpose verb, “chored”, as in, “I chored all morning. ” Making soap, making candles, upholstering chairs, mending. The mother of six, only three of whom lived, she uses the word weary a lot in her daily accounts. It is often underlined.

I’m reading her diary to better understand what life was like for people who lived here when these woods were pastures and farms. I want to pull back the wool of abstraction from the history of this landscape. Her diary puts new focus, too, on the intimate connection to nature that was her daily life. Life amid nature was not for her the walk in the woods I enjoy. It was a horrendous, unrelenting amount of work, wresting a living from the land in the era of horsepower and firewood.

By 7 AM the pasture and cowshed, apple tree and stonewall are awash in the even, first light of the day, a light without shadows, all promise and possibility. The stars are snuffed out, and soft pink light glows right at the tree line, while a blue grey shadow hangs lower, amid the trees’ trunks.

At 7:20, the sun touches the trees at the top of the pasture with a ruddy glow. The first beams glitter on the snow out my kitchen window as I put the muffins in to bake. Colors spangle the dry, fluffy snowflakes as they catch the low light: red, blue, green, orange. The wrinkled visage of the walnut shows now as the light penetrates the texture of its bark.

Sun gleams on the metal of the instrument tower poking up from the forest to the north. How funny that when I first arrived last August I was annoyed, thinking it was a cell tower invading my view. Only to learn it was the Barn Tower, instrumented with the devices we use here at the Harvard forest to track the seasonal progression and physiology of the trees – information at the core of my work tracking the life history of a 100-year old tree.

Two muffins down, and I was out the door into the majesty of a cold so deep it makes its own rules. I’ve not been often in weather that could kill, but who could resist enjoying the woods amid the sound and sparkle of a minus something degree morning, with a bluebird sky and radiant sun. I went to see my tree first.

The big oak waits out the winter cold, deep in dormancy. Sugars it stored last fall from its summer’s work of photosynthesis keep its living tissues from freezing now in winter.

This big oak I am exploring this year was stoic and still. There is something new here every day, and today, it is was a sound: the crack of trees, bearing the cold. In the quiet, a report sharp as a handclap told of the weather.

Trees are engineered to endure the cold. They recall sugars from their leaves in autumn before the leaves fall that work like antifreeze in winter. Glucose in the solute sustaining trees’ living cells keeps the water from forming ice crystals, even though the temperature is below zero.

Michele Holbrook, Professor of Biology and Charles Bullard Professor of Forestry at Harvard University explains the danger to trees isn’t a cold, dry, sunny day like this. It’s the ice storms that ravage trees. “An ice storm adds a lot of weight to the tree, and then you get some wind. Then you get a lot of damage,” Holbrook notes.

Ice is a vector of new life in New England forests. In an ice storm, trees topple and shed shattered branches, opening the land to light, and the trees waiting their chance to surge from the suppression of shade into their release at last, to openings in the canopy.

Winter is a force, no question: already, all around its base are the branches my tree has been shedding this winter, pruned by the wind. On a calm, cold day like this though, mostly, my tree is a silent sentinel, deep in dormancy, barely respiring, just waiting winter out.

I walked on, following an old wagon road through the woods, lined on both sides by streams. Frost flowers bloomed on the black, virgin ice formed just overnight, still so clear I could see the flow of the cold water underneath.

Yet even in the deep freeze of a day like today, everywhere there were signs of life. Moss on a rock poked up fresh and green through the snow. And amid the blue shadows of the trees on the snow was the tracery of animal tracks: squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, and birds.

I arrived at the vernal pool at Hemlock Hollow, to find a smooth disc of snow on its frozen ice. It was hard to imagine that in just a few months its melted edges will draw wood frogs, whose quacking call will be a first sign of spring. But for now, winter reigns supreme in these woods, in a white palace of ice, frost and cold.

THE VIEW FROM FOURTEEN DEGREES

January 6, 2015

I walked up through the pasture this afternoon past the cows slowly accreting snow sifting down from a pewter sky. Cowbergs, they struggled to their feet from a heaped, hulked snooze as I passed, hoping for a treat. On cold days I often hand-feed them rolls and molasses. They love sweet, cheap white hamburger buns best of all.

But I was on the way to my tree, so threw a leg over the board fence to head up into the woods. And there it was: The big oak I’m observing as a Bullard Fellow this year at the Harvard Forest, wearing its first snow of 2015. Now well into its 100th winter, it was flocked with white, the ridges of its bark filling with snow. At the base of its trunk, the deep clefts between the flares of its buttressed base sheltered oak leaves still dry and snug as a nest. A bit of tender, green fern even persisted deep in a hollow at its roots. I was amazed this tender plant of spring and summer survived in a sheltering nook of my tree, even as winter deepens. How many other plants and animals does it succor in the winter cold?

My oak is a generous monarch. It dominates its forest grove, but shelters the lives of many plants and animals, in every season, even a tender fern in deep winter.

The woods were the quietest I’ve heard them this winter. Snow stooped the young hemlocks, and piled up on frozen mushrooms sticking out stiff as shelves from the trunks of paper birch.

I thought as I walked about the anchor of landscape; how a single tree, or view, can be the hub of the wheel of our days. I’ve known this oak in every season now. Amid black flies and ticks; ice pellets and snow; the burning stars of winter nights; and the soft, tender full leaves of early June. On this, the first snow of the New Year, this tree was what I wanted to see.

The sun shone like a full moon through thick clouds, lighting snowflakes sailing across its beam. By afternoon, tender blue began to show amid the grey; the winter storm was clearing. My boots squeaked in the cold as I headed back through the winter woods, across the pasture. Today the high temperature was 14 degrees, and tonight will be colder. Strong stuff for a denizen of Seattle, where winter means rainy and 40. Here, my strategy is to wear everything I own, all at once.

Back at the farmhouse where I am living this year, the warm glow of the windows burned yellow. Evening was already edging in from the forest, which always darkens before the sky.

It was time to get some treats for the cows.

A FOREST NEW YEAR’S

January 1, 2015

The sun was radiant and the ground frozen hard as I walked up to my tree New Year’s morning. The stream ran along the Prospect Hill Road but as I reached the Barn Tower, ice was pushing out of the ground in translucent sculptures extruded by the squeezing pressure of the frozen ground. I splashed through mud puddles here just last week but the seasonable cold of winter has visited these last days.

This morning brought ice and frost patterns on the windows of the sun porch and I wondered if the cows would be frozen solid. Some New Year’s treats of English muffins with warmed molasses perked them up, along with a bale of fresh green hay.

A woodpecker was hard at it as I walked to my tree, a percussion section of one. There’s been no snow at all for days and I was surprised to see a bit of green fern hanging on in the sheltering cleft of the tree’s flaring trunk where it meets the ground. I know snow insulates it, but it persists even now in the cold, bare ground.

The cows are enthusiastic for a treat of English muffins and molasses. Happy New Year to them! Their tongues are rough as a cat’s. Something I did not expect to learn on my fellowship, but there you have it.

I notice the sun brings the birds. Yesterday at noon, my eye was drawn by a glint of blue: a pair of bluebirds, first one on a fence post, then the other in the red maple by the house, the sun flashing on the male’s wings. He came to the little stream that winds through the pasture to drink, tipping his head once, twice, to its glittering water. How important this stream is! How much life it draws. Also the seeds of the red maple, and the sumac, and tall summer flowers and grasses now faded to rustling scribbles of brown. So little is needed to sustain so much, this bit of cover in the thicket, a rivulet of fresh water, a bit of foraging ground in the trees and brush we hardly notice, but so vital to the animals of our winters.

The big oak I am studying this year was bathed in tender winter light. The sunlight was soft, yet penetrated deep into the bark. The shadows come so early now, and the textures of the woods are thrown into a richness by the angle of the sun I never see in spring or summer.

With holiday closure of the forest’s field station, the woods seems a special remove, the animals nearer, the trees too. A few walkers visit to enjoy the trails, but mostly, this is the forest’s quiet time. At night the great wheeling array of stars rewards an outpost here far from city lights. I listen. I take long walks.

A pre-dusk hike yesterday with my husband Doug brought the rewards of the sun-rouged cliff at Porcupine Ledge, the ice sculptures of rocks in Rutland Brook, worth a pilgrimage in itself.

Surrounded by wild lands in every direction owned by the Harvard Forest and The Trustees of Reservations, the trails at Rutland Brook, owned by Mass Audubon, are a sanctuary for wildlife. And people, too.

A WINDOW INTO THE ANIMAL WORLD

December 24, 2014

With a tug, this morning I pulled the bungee cord tight, attaching a wildlife camera to a tree near the big red oak I am studying this year at the Harvard Forest. My tree’s neighborhood is now under surveillance.

Is my tree the most-monitored red oak in history? BT QURU 03 is a tagged, tracked research specimen in a long-term study of the seasonal gyre of the forest. Every week, during fall and spring, John O’Keefe, Harvard Forest field phenologist, checks the status of its canopy, noting when in spring its buds swell, leaves open, and grow, and then in the fall, when they color, and drop. The Richardson Lab at Harvard University monitors the tree’s canopy and environment with an array of instruments, including a Web cam on a tower observing the forest where it grows. And I am tracking it too, with another Web cam purchased by the Knight program in Science Journalism at MIT.

Some of my collaborators here at the forest helped me set it up right at my tree’s trunk, to observe this tree’s individual canopy through the seasonal year. Images from the Barn Tower Web Cam on the tower, and the Witness Tree Web Cam at the foot of my tree are uploaded to the Harvard Forest web site every half hour, during daylight hours, 24/7. Have a look.

Now, thanks to David Foster, director of the Harvard Forest, there’s a wildlife camera on the case too. It’s a good camera. Set to take a photo anytime it senses motion, it will record the doings in BT QURU 03’s realm.

I put up a wildlife cam this morning to keep track of the animal doings in my tree’s neighborhood. Thanks to David Foster, director of the Harvard Forest for this new look into the world of my tree.

Why all this attention? This big, grand tree is the main character in my book, Witness Tree, which I am researching and writing while a Bullard Fellow this year at the Harvard Forest. I’m taking a deep, long look at the tree’s 100 years of human and natural history. Already I am learning that in my micro-history of this one tree, in this one place, there is so much to see: our changing relationship with nature, and even our changing world. Scientists here at the forest know, from long term research, that spring comes here earlier now, fall later, and winter is squeezed on both ends. They know my tree sprouted by a stonewall in about 1905, maybe earlier, the core we took from the tree last June did not reach to its heart.

My tree has witnessed so much change. Its forest is the third in this region. The pre-colonial forest was cleared by European settlers beginning in about 1700, to begin subsistence farming. The chopping continued relentlessly, until about 1830, with about 75 percent of the forest felled for pastures and farm fields. But better transportation was the death knell of small farms clawed from the stony soils here in New England. With the Erie Canal, railroads, and expanded road networks, markets were opened to the better farmlands of the Midwest. Most farmers here abandoned agriculture. Their fields naturally seeded in to almost pure stands of white pine, from the big trees left in corners and borders of the pastures and farm fields.

By the early 1900s, those trees were slicked off too, for boxes, barrels, and more, with loggers using portable mills to saw the trees where they were felled. Then the next forest grew up, the hardwoods and pine we see in the Harvard Forest today – including my oak. A wild sprout, it took root by a stonewall along what since at least the mid-1800s was an unimproved pasture, land use records at the Harvard Forest Archives show.

Along the way, our carbon love affair was cranking up, with millions of Model T automobiles pouring off assembly lines, and people leaving the farms and woods for good, making their living in the industries that both bettered, and worsened our world. The level of atmospheric C02 when my tree sprouted was about 300 parts per million. Today it is 403 and counting. Scientists here can see the physiological effects on the forest. Long-term observations show the faster growth of red oaks – the dominant species in the Harvard Forest — and the destruction of others as temperatures warm, stoking invasive pests. Every hemlock in this forest is expected to be gone within a generation, their lovely, feathery foliage eaten to bits by hemlock wooly adelgid.

What of the animals?

Interestingly, they have been the winners, as New England forests have grown back, in one of the most important reforestations, albeit accidental, in the world. The degree of landscape change in New England over the past 300 years is hard to overstate. The Harvard Forest is a perfect example. Today, this nearly 4,000 acre forest, once a place of broad, sunlit meadows and strolling cattle, lies within the most forested region of the US, with forested connections north through New York into Canada creating critical pathways for wildlife travel.

This is the view the wildlife camera will be monitoring. Trees have returned to the pastures and farm fields once delineated by these old stone walls. And with the trees, have come the animals: bear, moose, deer, wild turkey, beaver, and more.

For as the trees have come back, so have the animals, both through natural migration, and purposeful human reintroduction. Rare enough to warrant a journal entry in the time of Thoreau, deer today are virtual pests. Wild turkeys, bear, moose, coyote, bobcat and beaver populations, all rare or totally absent in the mid-19th century, are booming. Meanwhile, open field species, such as the bobolink meadowlark, are on the decline.

These are not the same forests European settlers first encountered. There are no wolves, for one thing. And the forests are younger, and of more even age class. Missing are the gigantic trees of the pre-colonial forests. And the composition is different, with fewer beech and hemlock, those monarchs of shade. And of course there are no chestnut trees, and no passenger pigeons. It is poignant to read in Thoreau’s journals of the great roosts of these birds in the forests of New England, and the sound of people beating chestnut trees, to shake down their nuts. Sounds we will never hear.

I’m curious to see which animals will show up in the eye of the wildlife camera. Will it be only chipmunks on the stonewall, caching acorns? Perhaps moose or bear will grace us with their presence. One thing I tried to avoid, by pointing the camera away from my tree, and toward the deep woods, is lots of pictures of me.

I think I’ll move the camera monthly, to give it different views and perspectives. It is not baited, by the way; I didn’t want to create a snack bar. Instead what I want is just a little window into my tree’s world. I’ll check the camera every month, and post whatever photos of animals it takes here in the blog.

In the secret life of the night, the quiet dawns, which animals come to visit? What company does my tree keep? I can’t wait to find out.

A SOLSTICE SNOW SHOWER

December 22, 2014

The winter solstice arrived with a spangled snow shower today, with bright sun casting my shadow on the fresh snow even as it fell. The individual flakes were minted in flat, sparkling perfect forms, no two alike. Six-armed, four, flowers, crystals. They melted to softness within seconds. Like the velvet in a jeweler’s case, the black fleece of my glove showed them to perfection. Likewise the black wool of my coat.

My black fleece gloves were like a jeweler’s black velvet display case for today’s spangled snow shower.

What a surprise gift, this snow. Our forecast this week is for unseasonable warmth, even rain. Indeed later today it warmed and misted; how glad I was that I let impulse guide me out the door, to see this beauty as it arrived. It was the snow that drew me out.

I began at the pasture. Our little herd of cows is dwindled to just two, the others taken to their home barn for the winter. It was quite the rodeo of recalcitrants, these two are the ones left as it became too dark to keep at it last Friday. I have been babying them all weekend with fragrant bales of fresh, green hay. How dear they looked, the two of them, back to back, sharing warmth in the upper pasture as the snow came on. John Wisnewski, head of the Harvard Forest Woods Crew, owns these cows and teases me that people give them attributes they don’t have. But really, don’t they look like cozy friends?

I went on into the woods to see what I might find on this winter solstice day, one of my favorites of the year. I have been watching the sun in its procession ever southward since the fall. It is now so far south that as I sit at the picnic table at the front meadow to write in my morning journal I must turn my head over my right shoulder to even find it. In the glassed-in porch, where I retreat on cold or wet days, it now fills the furthest south window, and its rays have a mellow light that comes with the lower slant of winter.

Why do we begrudge and rush this time! Everyone celebrates spring, summer and fall, but what of winter? The solstice brings such a gift of long dark nights, and the quiet of winter woods into which we can see so much further, into its secret places, with the leaves down. The animals seem more present. We can see their tracks now, and on the clear architecture of the trees’ bare branches, the birds show themselves.

This morning as I opened the door to get the newspaper, there was a barred owl on the lowest branch of the black walnut out front, scanning the thickety-thick of brush along the split rail fence bordering the pasture. Silently, the owl swooped to the sugar maples to the west, and perched, surveying its domain with an eerie head swivel. So quiet was the morning, with not a breeze stirring. This owl seemed conjured, a vision, gone nearly as soon as I saw it.

Deeper I went into the wood, finding that the beeches, still holding their leaves, became scoops for the falling snow. The pattern of autumn’s leaves on the forest floor was quilted with white.

The last leaves on the beeches became scoops for falling snow that softly flocked the hemlocks behind them.

The limits of photography are interesting. Over and over I took pictures of the grace of the snow easing from the sky across the dark green hemlocks, and not a one renders the peace and beauty of that moment. Likewise the sparkle of the snow. I lay down to try to capture it face on, at its level on the ground, and while a bit of the sense of it comes through, it’s nothing like the glim of the feathery, evanescent sparkle of this snowfall. Some things you just have to experience.

The feathery evanescence of this snow shower was like a walk in a snow globe. I’m not sure any photo could capture its delight.

Likewise the peace of Hemlock Hollow, at the halfway point in my walk. At its vernal pool, the delicate line of newly formed ice was traced by the snow, and I had the conversation of a single chickadee for company.

At the end of my walk, I stopped by to visit my big oak and clean the snow off its camera. The trunk was dusted on the windward side with fresh snow, and the hollows in the bark filled with white where the tree flares to the ground. Snow sailed across the grey of its wizened trunk, and a few last leaves still clung to high branches, showing me the direction of the wind, blowing from the southeast. I remembered well the low sun of the fall equinox, which I also recorded at my tree, wondering then what the winter solstice would bring. And now I know: beauty, and peace.

In Praise of Trees

December 20, 2014

Now comes our time of year when we decorate and pay homage to our dear traveling companions in this life, trees. Cedar, hemlock, fir, the whole great evergreen nation are swept into our collective solstice/holiday craving for light, as nature’s colors dim and the nights comes on early, dark and deep. To me, holiday lights on trees, inside or out, are among the loveliest practices in this, our winter time of celebration.

Here at the Harvard Forest, after what I am told was a long dry spell, we have a tree, cut from our very own woods by John Wisnewski, of the Harvard Forest Woods Crew.

Our tree in the Common Room at Shaler Hall, cut from the woods at the Harvard Forest and decorated by the staff.

I love this tree. Its soft glow, and home made decorations are just the sort of simple beauty I enjoy and its light through the windows at night is a sight to behold, particularly on snowy nights.

But why only now do we turn to trees to be enthralled? Is their beauty not with us always, and to be held before us daily in ardent gaze? Here is the poet Mary Oliver, in lines sent to me by my editor Kathy Belden at Bloomsbury Publishing, thinking of me out here in the woods.

The Trees

Do you think of them as decoration?

Think again.

Here are maples, flashing.

And here are the oaks holding on all winter to their dry leaves.

And here are the pines, that will never fail, until death, the instruction to be green.

And here are the willows, the first to pronounce a new year.

May I invite you to revise your thoughts about them?

Oh, Lord, how we are all for invention and advancement!

But I think it would do us good if we would think about

These brothers and sisters, quietly and deeply.

The trees, the trees, just holding on to the old, holy ways.

–Mary Oliver

Doesn’t she get it just exactly right? Oliver in customary brilliance nails one of the things we love about trees, not only at this time of year, but always. Their keeping of the old, holy ways. It is their steadfastness, their hopefulness, and stoic vigor she dials in, and invites us to cherish.

And so as you enjoy the glimmer of holiday trees, think too of the luminous beech, bright when all the other trees have passed their fall brilliance.

John O’Keefe, Harvard Forest field phenologist, in the glow of a beech, the last of the trees to lose their color in autumn

Of the fresh spring leaves on a striped maple, so soft to the touch.

Think of the wise counsel of a great oak, like the one I am studying this year.

And so give thanks for the trees, with us not only now, aglow in this last breath of this year, but always, worthy of our upswept gaze and rapt appreciation, in all the months and seasons of our lives. This spring cut fresh buds and unfurling branches; in summer, decorate your home with verdant green boughs. Come fall, bring in the brilliance of autumn’s palette to your house, luminous as any holiday tree. All winter long there are the spicy hemlock boughs to lay on our windowsills, clip for hot tea, and the cleansing withes of cedar, and long, soft needles of white pine, each ours to enjoy. How lucky are we, for the beauty of trees, every day and month of the year.

PRACTICE MAKES…BETTER. CLIMBING THE BLACK WALNUT

December 19, 2014

What does a tree feel like in winter?

There was only one way to find out, I figured, so last weekend, up a black walnut I went. Higher and higher, above the roof of the house where I live, knocking snow off limbs as I went. And getting snowed on too, by my climbing companions above me.

This all got started last year when I committed to looking long and deep at the life story of a single, 100-year old tree at the Harvard Forest. I knew then I would want to climb that tree — and that it would take professional help. It’s a tall order, literally, a big red oak, more than eight stories high, with no branches at all for the first 40 or so feet. Pretty intimidating. But I was going to be at the Harvard Forest all year as a Bullard Fellow in forest research, writing my book, Witness Tree. I figured getting my arms around it – literally – was part of what I was in this for. My dream ultimately, we’ll see if I manage it, is to get comfortable enough to write up there. Go up with my notebooks and sketch, and take notes, record birdsong, maybe even haul up the laptop and have at it. Why not write from the trees? What would it be like to spend an afternoon in a tree like that, to be part of its canopy life?

Melissa LeVangie, the tree warden for Petersham, gave me my first climbing lesson last month, gamely getting me way up into the tree on a first visit, using a climbing harness and ropes. It was an overwhelming, heart pounding fraught peril, this hauling of myself up the rope, or so it felt to my novice self (Melissa made sure I was always utterly safe.) Yet I found, as I made my way into the first branches way up the oak’s trunk, that I liked it up there. I loved the feeling of standing way up in its world, on its terms. I was hooked. We decided to schedule another climbing lesson. This time, we brought reinforcements.

Melissa’s twin sister Bear LeVangie, a champion climber, and two friends from the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT, Rachael Buchanan, a producer at the BBC, and Patrick Wellever, digital media training coordinator for the KSJ program, strapped into harnesses too.

A tree in winter is a different being. I know this tree well: the black walnut we were climbing is right outside my front windows at Community House, where I am living. The walnut tree is the first thing I see every morning when I get up, and the last thing I see on my way to turn in for the night. Like all black walnuts, it is a spectacularly symmetrical, vase-shaped tree that wholly dominates its space. Black walnuts actually emit a chemical from all of their parts that discourages the growth of plants under their canopy. Uncrowded by competition, each branch tapers to twigs and twiglets in perfect fractals. The tree is a math made visible.

The symmetry and low branching habit of the black walnut makes it a good practice climb. Getting started, “low and slow,” at Melissa’s advice.

I’ve watched this tree closely through four seasons, it crowns the meadow where I write in my journal in the morning and evening at a picnic table; it fills the windows of the porch where I write when it’s cold, and it towers over the firepit where we gather sometimes at day’s end. It is festooned with tresses of compound leaves in the spring, aglow in yellow in the fall, and alive with squirrels and birds cruising for nuts as winter comes on. (I saw only two walnuts, this year, visible at the very top of the tree only briefly, before some animal snagged them.)

Winter though is when this tree takes on the spare beauty of a pen and ink drawing, or Japanese scroll painting, all black clean lines that in fresh snow wear an ermine robe.

It had snowed the night before our climb in the walnut. The perfect tree for a training climb, Melissa and Bear picked it for its accessibility. Unlike the fierce oak, this tree had branches almost low enough to touch, and arranged in a regular array that allowed us to climb not only rope, but the tree itself.

With daylight hours short, we got right to it last Saturday morning, at 9 sharp. Cinching our harnesses tight, pushing the tension knot up the climbing rope, and paying out the rope’s tail, up we went, feet off the ground in a dizzying first jolt. Melissa put an ascender on one of my feet so I could push down with my legs to add power to my arms. Up I went, zip, zip, zip. My neck tingled as Rachel, already way above me, stood on a limb over my head, releasing crystal flakes sparkling in the sunbeams and sifting down inside my collar. I knew Patrick was going to be a natural, and sure enough, he was already way above us both, higher than the roof of the house, up where the walnut tree’s trunk starts to narrow.

That’s what I wanted to learn, the physical geometry of the tree, how it felt in my hands and under my feet. And its branches, what would they be like in the cold snowy day? Stiffer. Rigid. The moss on the limbs was packed with snow that caked our ropes. I placed my feet with care as I stood on a limb, and looked out to the pasture I had never seen from up here. The lines of the paths I know so well coalesced in overview, and the cows, as they chewed their morning hay, looked on with seeming curiosity. Whatever would those humans do next?

I knew Patrick would be a natural and he was. On the ground in the distance, the cows take in our antics.

Melissa reminded me to face the tree and its architecture, see that I could climb it, and not just the rope. I raised a leg, kid style, to clamber higher, pulling myself up on the bough overhead. I hadn’t done that since I was about 7, I thought, and as I climbed, the memories flooded back. It was the Eastern red cedar by the frog pond where I grew up, and one day, instead of just leaning against its trunk with a book, up I went. What stayed with me all these years later was the memory of two things: how the view of my world shifted, with my aspect from up high. I was thrilled by the secret world in the tree I discovered, including tiny blue-green berries that grew only up top. But best of all, and I remember it still, was my sense of sovereignty up there. The top of that tree was the first space I had defined for myself, all on my own. I came down when I was good and ready. For dinner, of course.

Melissa’s instruction enabled me to recapture the joy of climbing trees. I want to get good enough at this to enjoy writing aloft in the big oak. We’ll practice every month to savor the trees in the seasons. They feel — and sound — different, month by month. Next time, Patrick and Rachel are going to be packing heat: a GoPro and digital camera to film video.

In the afternoon, we practiced throwing the line into the walnut as if to begin a climb. We tossed a small, weighted bag attached to the orange nylon line with a cat’s cradle maneuver that cranked the momentum of our throw before releasing the line with a hissing swish.

I was cocky about this; I spent hours daily playing catch as a kid, wearing a patch into the front lawn down to dirt where I stood, opposite my brother Matt, whipping a baseball with my long gangly arm and catching it with a satisfying thwack in my leather glove. Sure it was, well, decades later. But still, I figured I’d be an ace with a throw bag.

Wrongo.

The branches catch at the line. And yanking it, I learned, perfectly wedges the bag into the no-man’s land of the tight little nook where the branch joins the trunk. Pull harder, and it sticks…tighter, Chinese finger trap style. Melissa finally had to harness up and go get the thing.

Cold, but exhilarated, we called it a day. The sun was sinking into the trees as we helped Melissa and Bear pack up their gear, and the black walnut was already in evening shadow. The last sun burned on the upper pasture, leading to the woods. Right where this, we all knew, is headed. Next month, we’re tackling the big oak.

WATER: THE VOICE OF HISTORY

December 17, 2014

I went out into the wood at midday to see what’s new. It’s warm here today, 45 degrees at noon, and overcast, with soft robin’s egg patches of blue breaking through the grey. The cows at the Sanderson Farm outside Community House where I live were snoozing in the south facing upper pasture. Norma, the bossiest, turned her head as she heard my door open, watching closely to see if I approached their fence. If knew if I did, they would all come over, looking for hamburger rolls or English muffins – their favorite treat. I walked on so as not to rouse them, aware Norma watched my every move as I passed along the edge of their pasture that fronts the Locust Opening Road, the main entrance to the Harvard Forest, closest to the parking lot.

The cows’ charisma is universal. Living here, I am aware of most visitors when they arrive and what they do. Invariably, as they head to the woods for a walk, or for research, they stop at the fence, and visit the cows. So popular are the cows that the Woods Crew had to post signs on their fence about the baby cow that likes to come under the lowest rail and take itself for walks and snack on fresh grass and the bales of hay waiting to be pitched over the fence for tomorrow’s breakfast. The sign assured visitors new to our little world here that the calf will take itself back inside the fence with the others on its own. “We were getting so many calls,” says John Wisnewski, head of the Woods Crew, and owner of our little herd.

One of two baby cows at the Harvard Forest helps himself to a snack while the rest of the herd looks on. The cows are so popular the Woods Crew had to post a sign assuring visitors the calf finds its way back under the fence when it’s good and ready to rejoin the others.

The cows are not only ambassadors for the forest, but a full time cast of historic re-enactors. With their sauntering gait and round the clock mowing, they not only keep open the pasture that would otherwise grow up into trees, but maintain and re-create the historic landscape of the John Sanderson Farm, here before Harvard purchased this land in 1907 for the Harvard Forest. This pasture today with its view of strolling cattle, stone walls and woods, is a deliberately recreated historic landscape, to show visitors what most of the New England landscape for many miles around would have looked like from about 1830-1880, the height of agricultural clearing in the region. The dioramas as the Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest tell this story vividly.

Agriculture on these poor soils and small farms could not compete with the farms in the Midwest, once railroads and the Erie Canal opened markets to the populous markets of the East. Abandoned and grown back to trees, the former farmlands here are the forests we study at the Harvard Forest today.

Walking these woods today I see leaves still clinging to some of the oaks, but mainly it is the beeches that hang on, their leaves a bright toast color. Last week’s snow is melted in the south facing and open areas, but still heaped in the shadows and corners and canopied glades.

Moss on the stone walls and tree trunks is positively fluffy with the cool, moist weather, and the green of lichen, white pine and hemlock so lost in the foliage of the forest the rest of the year is vivid now. The white of paper birches is a clear bright note, a flute in the forest’s double bass brown, grey and wine color chords as we edge toward the winter solstice.

I realize as I walk and look that what is really before me is not one season, but four. Summer’s leaves on the ground, in fall repose, and spring’s buds clasped on winter’s bare twigs. Such a visible reminder of the seasonal procession that never stops, that we are privileged to see in our own brief moments in nature’s pageant, is a comfort. So are the rock walls and abandoned pasture gates and cellar holes I pass, reminders of our human seasons of use in this landscape, in an inextricably intertwined human and natural history.

The remnants of snow wear a pelted pattern drilled by falling drops of water from the high branches of sugar maples and oaks that line this portion of my daily, three-mile circuit in the wood. Leaves where the snow has receded are a rich, wine-dark brown; they aren’t the glossy, slippery dry scatter of just a few weeks ago that raised a ruckus of a rustle as I walked.

I see a lovely scatter of berries on the ground then feel embarrassed to realize they are the fruit of bittersweet, an invasive vine winding like an anaconda around a red maple. I remember I am not supposed to like it.

How the beech leaves blow, letting me see the wind, their flutter telling its speed and direction. But mostly, the leaves are off the trees now, and the snow gone from their branches, allowing me to see deep into the wood. And now, with the leaves off, there’s also this: the sweet sound of running water, returned to the wood.

The amount of surface water greatly increases in the forest once the trees go dormant. The melted snow, the rain, and the groundwater instead of being taken up by the trees for photosynthesis and passed into the air as water vapor, gathers in pools, puddles, trickles, rills, streams, and vernal pools. The vernal pool I watch through the seasons with John O’Keefe, Harvard Forest’s field phenologist, is filled brim full today. Its white ice is melted at the edges, where the transition from frozen water to liquid is as soft and hard to discern as the edge of a cloud.

The vernal pool on my walk has been brim full since late fall, when I took this photo of ice just starting to form. The pool’s water level is driven largely by the seasonal cycle of the forest.

The seasonality of the water level in this pool is what makes it a vital habitat for amphibians. Unable to support fish, it’s just the place for tadpoles of wood frogs to rear, metamorphosing to their terrestrial state before the pool dries out in summer. These still, clear waters are alive with the odd, quacking sounds of breeding wood frogs as soon as the first margin of meltwater shows in this pool. It’s an important, brief season of life entirely dependent on the water cycle cranked by the forest.

Seeing and hearing all this water around me now is a reminder of just how much moisture the trees soak up when they are at work. The path I walk through the hemlock wood is awash in puddles; usually I can hop rocks through here, but today I must pass deep into the wood beyond the path.

On the Prospect Hill Road, a stream winds downhill to the upper pasture as I head back toward the house. The cows know this stream well, after a dry spell, they will head to it for it to drink when it rains, passing up their water tank. Perhaps it tastes better, or they just like the change.

The view and sounds of all this water I enjoy today is a seasonal pleasure – but also a look and listen back to the history of this landscape. Back when all the trees I walk through today were cut for pasture and crops, the streams ran big enough to turn mills. That’s hard to imagine today, when the forests are using the water. But what we take for reality is just today’s version of this forest.

John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest, notes how high the water level has risen at a seep on the path we walk, as the trees shut down for winter.

Not long ago, these streams ran hard enough year-round to turn millstones crushing tannin-rich hemlock bark, to steep with hides in water-filled vats, processing them to leather. John Sanderson ran a tannery turning out some 1,000 hides a year on this land. Amid the trees grown up since, if you know where to look, you can find the olds vats and millstone of the Sanderson tannery.

Today, the mill is long gone, but in winter, that same stream runs high and full, and the woods are full of its sound. The dormant trees have released it from a spring and summer industry of their own, making wood from thin air.

THOREAU, REVISITED

December 15, 2014

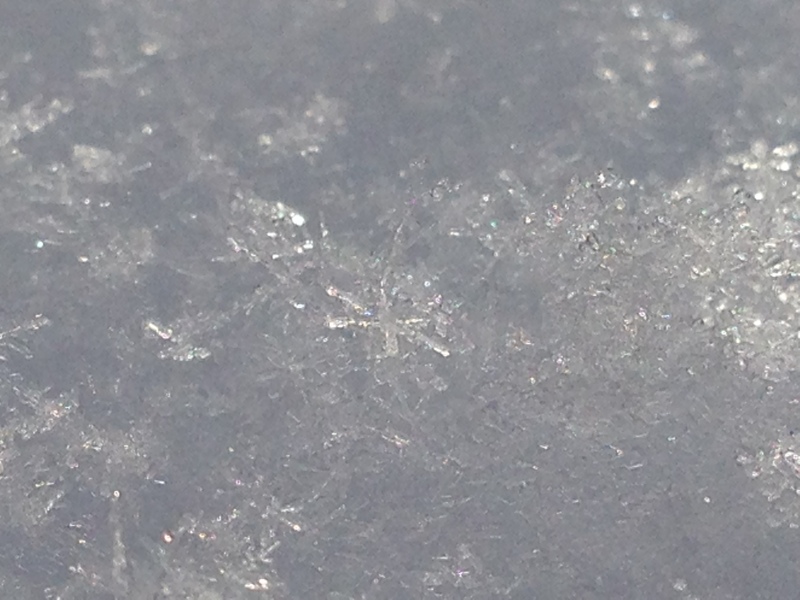

“This morning it is snowing and the ground is whitened…looking more closely…I found that it was sprinkled all over… with regular star-shaped cottony flakes with 6 points…It snowed geometry.”

That was Henry David Thoreau’s observation from a winter walk he recorded in his journals during just about this very same week in 1855. I like to read Thoreau’s journals just to check in on what he was doing on the same day I’m here nearby in a similar landscape at the Harvard Forest 159 years later, taking my own deep look at the woods and its denizens.

The very day I read this, I had taken my own note of the geometry snowed outside overnight, with a fresh four inches of perfection.

“It snowed geometry,” Thoreau wrote on Dec. 13, 1855. His lovely phrase is just as apt today to describe this fresh snow I photographed at the Harvard Forest during the same week he wrote that, 159 years ago.

Thoreau went on that day to note what I call nature’s newspaper: The record of the life of the forest written in freshly fallen snow.

How winter opens our eyes to what is going on all the time around us that we do not see. Odd that we call it the dead of winter, when so much doesn’t die at all, and our own lives are actually expanded by winter in so many ways. Not only in what we can see, but in where we can go. All sorts of places off limits during the rest of the year suddenly become broad playgrounds we can access on the ice. But best of all to me is the sudden opening of a picture window into the world of animals that snow provides. Here’s Thoreau again:

“The sun has quite melted the thin snow on the south sides of the hills – but I go to see the tracks of animals that have been out on the north sides—First getting over the wall under the walnut trees on the south brow of the hill I see the broad tracks of squirrels, probably red, where they have ascended and descended the trees – and the empty shells of walnuts which they have gnawed left on the snow – The snow is so very shallow that the impression of their toes is the more distinctly seen – It imparts life to the landscape to see merely the squirrels tracking the snow at the base of the walnut tree. You almost realize a squirrel at every tee. The attractions of nature thus are condensed or multiplied. You see not merely bare tree & ground which you might suspect that a squirrel had left – but you have thus unquestionable & significant evidence that a squirrel has been there since the snow fell – as conclusive as if you saw him.”

The very same day I observed my own six-armed snow geometry, I had also marveled at the tracks at the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. How the snow revealed the animals’ busy run to the stash of acorns at its base!

The big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest, the morning after several inches of fresh snow. What busy animal doings are recorded on its fresh, white page!

Aficionados can read Thoreau’s lovely passages for themselves in his journals published online, a great service to readers of the University of California at Santa Barbara for their accessibility, with typed transcription of Thoreau’s handwriting. To enjoy these passages, open the link and browse pages 214 to 218.

What is it about walking? It opens the mind and eye in a way few other things do. Thoreau of course was on to this, and we can all learn from his ambulatory study of the world around him. Part of what I most enjoy in being here at the forest is the pleasure and privilege of long daily walks, to see what nature is up to – and to feel the continuity of this simple pleasure, undiluted by the passage of time or history or technological change since Thoreau wrote, and long before.

For all that has happened since Thoreau struck off on that winter day December 13, 1855 recorded in his journal, nothing has changed in the delight of the geometry of a snowflake, or the wonder at the animal lives revealed all around us by tracks in fresh snow.

Someone’s been raiding their winter stores of acorns at the base of the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. The snow reveals the lives of animals usually hidden all around us.